With street art so prevalent in cities and urban areas around the world, it’s sometimes easy to forget that it is, by definition, illegal. This art form often stirs debate within the art community and among the general public, with views varying on whether street art enhances urban environments or is merely a form of vandalism. Regardless of the different perspectives of street art, there is no denying the level of skill, imagination and daring required to create such art, which often portrays socio-political issues, personal experiences or cultural identities. Whilst it’s easy to think of street art as a relatively newer form of art, history shows that humans have been creating similar works for thousands of years, whether it’s paintings on a cave wall or tags in a tube station.

Recently, there has been a growing movement to legitimise street art by commissioning renowned artists to produce large-scale works in public spaces, such as Stik’s 2013 work ‘Liberty’ in New York City, to celebrate the area’s history of activism. In addition to visually brightening up city streets, commissioned murals often focus on the local history and demographics in a celebration of the culture, or to make a statement on social changes in the neighbourhood.

However, not all street art has been welcomed into city centres - even from acclaimed artists. Owing to its largely-illegal nature, the creators of urban art in public places have often been arrested, fined, and sometimes even jailed for their work. Read on for the stories of five street artists who took the risk for their art.

French-born, Berlin-based artist Thierry Noir moved to Germany’s capital in the early 1980s, inspired by the same pilgrimage that David Bowie and Iggy Pop took in the previous decade. Before turning his hand to street art, Noir himself was in a band in Berlin’s underground music scene, before implementing the city’s largest and most daring feature as his canvas - the Berlin Wall.

In 1984, Noir teamed up with fellow French artist, Christophe-Emmanuel Bouchet, to transform the ominous concrete barrier into a symbol of hope, whilst risking arrest from the border guards. Noir’s art also raised suspicion amongst local Berliners, who suspected the artist of being a spy or working for the CIA. Ultimately, Noir’s creations gradually earnt him respect from the residents of Berlin, after he’d painted around six kilometres of the Berlin Wall before it was brought down five years later.

Despite the fall of the Berlin Wall, segments of it still remain with Noir’s trademark side-profile characters painted on the surface, on display in both public and private collections.

Click here to see original Noir works salvaged from the Wall sold here at Tate Ward Auctions!

Now regarded as a pioneer in graffiti art, as well as a gay rights and AIDS activist, Keith Haring brushed arms with the law during his early years. Instead of using paint on walls, Haring put his own spin on street art by incorporating the black paper of unused subway advertisement boards with white chalk to create his trademark outlined figures. In the early 1980s, Haring would gain his initial recognition by creating these free and fast artworks in New York’s subway stations, which he saw as his ‘laboratory’ and ‘the perfect place to draw’, quickly garnering fans who came to recognise his distinct style.

Unlike other graffiti artists who would work at night to escape arrest, Haring enjoyed creating these drawings during the day so he could interact with New Yorkers and make his artwork accessible for everyone. Haring’s simplistic yet bold technique was perfect for the efficiency he needed to create these works - he had to complete his drawings as quickly as possible with no preparation, without being arrested. However, Haring was often caught and fined numerous times, stating: “more than once, I’ve been taken to a station handcuffed by a cop who realized, much to his dismay, that the other cops in the precinct are my fans and were anxious to meet me and shake my hand.”

Over the space of five years, it is estimated that he created approximately 5,000 pieces in New York’s subways, with the majority having been torn or covered up by adverts.

Click here to see original subway drawings sold here at Tate Ward Auctions!

Another street artist with a different spin on the medium is French artist Invader. Rather than using the standard spray paint to create his works, Invader implements and arranges small tiles into pixelated characters, like Roman mosaics made contemporary. The 8-bit style was inspired by the villains in video games that Invader played growing up in the 1970s and 80s, in turn inspiring his pseudonym.

Calling his installations ‘invasions’, Invader places his works in culturally and/or historically significant locations, such as on the Hollywood sign to mark the millennium panic. Like Haring, Invader believes that art should be available for everyone and therefore displays his work on the streets so that the general public can view it everyday.

However, Invader works largely at night and keeps his identity well-hidden to avoid arrest and maintain an air of mystique. Additionally in 2015, while planning another "invasion" in New York City, he requested, via social media, for building owners who would be willing to host his works legally to avoid any legal action. So far, Invader has never been arrested, largely owing to his anonymity.

Click here to view Invader works sold here at Tate Ward Auctions!

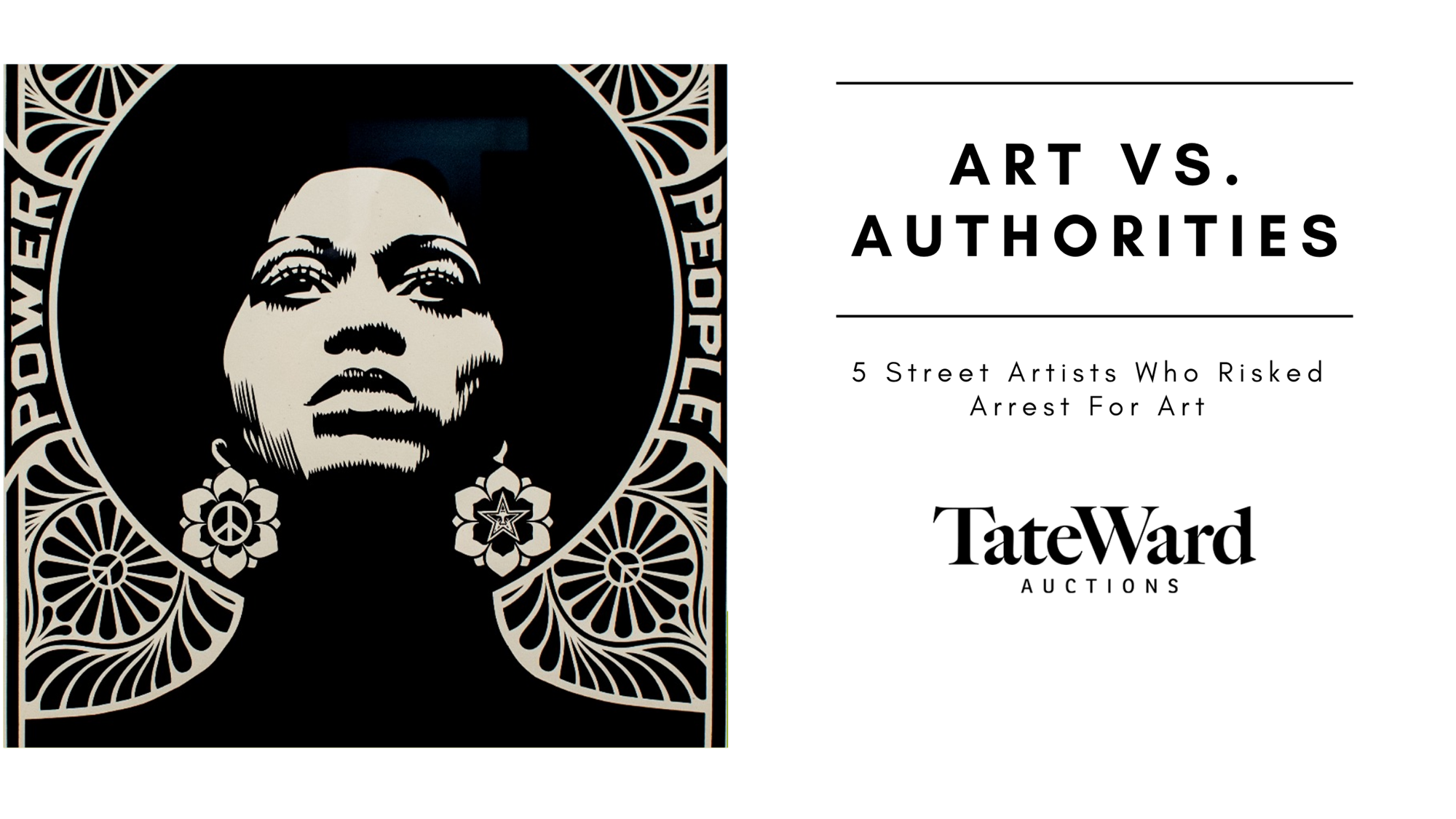

Fairey’s work often features high-profile people, with his memorable poster of Barack Obama for his 2008 candidacy receiving a thank you message from Obama. He also donated money made from the poster sales to organisations such as ACLU and Feeding America.

As of 2015, American artist Shepard Fairey had been arrested around seventeen times in the then-twenty years he’d been a practicing street artist. Fairey seems mostly unfazed by the threat of jail time, stating that - alongside his commissioned murals - he still plans to “do stuff on the street without permission”. Most memorably was his 2015 arrest in Detroit, where he allegedly caused $9,000 in damage by illegally leaving his posters on private and public buildings - after completing an 18-storey mural he was commissioned to do.

Fairey also founded the streetwear brand OBEY, which incorporates socio-politically motifs into their clothing, to reflect Fairey’s opinions.

Click here to view Shepard Fairey works sold here at Tate Ward Auctions!

Hailed as the ‘Father of stencil graffiti’, French street artist Blek Le Rat took his inspiration from the graffiti artwork of 1970s New York and artists such as Richard Hambleton. Beginning his art in the 1980s, Blek began with his trademark rat stencil on the walls of Paris, an animal he describes as “spreading the plague everywhere, just like street art”.

He used the moniker of Blek Le Rat to mirror his art and maintain his anonymity - until 1991 when he was arrested for painting in the street. Consequently, Blek sped up his street art process by pasting up pre-stencilled posters in order to be quicker and avoid being arrested again.

Like other street artists, Blek also focuses on socio-political issues, such as his 2006 series focusing on the issue of homelessness to raise attention to what he considers a global problem. Similarly like other street artists Haring and Invader, Blek also prefers having his work on the streets as opposed to galleries, believing that integrity of an artist is to be seen by as many people as possible, not being sold or recognized in a museum.

Click here to view Blek Le Rat works sold here at Tate Ward Auctions!

Ultimately, whether viewed as art or vandalism, street art continues to challenge traditional notions of art and ownership, inviting an ongoing conversation about its place in society. As urban landscapes continue to evolve, so too will the role and perception of street art, ensuring it remains a dynamic and influential aspect of contemporary culture.

What do you think about street art? Entertaining, or a public nuisance? Let us know on Instagram at @tateward_auctions!